Why framing matters as much as accuracy in science communication

.jpg)

In today’s age of digital information, it is widely recognized that science does not speak for itself. Yet, taking this even one step further, the proactive dissemination of facts (whether it be through the media, social media, or other platforms) is also not enough to effectively inform the public or shift broad understanding.

The reason: misinformation is not a content problem, it’s a framing problem.

Misinformation persists because evidence is delivered without the infrastructure and context needed for it to be understood, contextually-supported, and trusted. Facts are interpreted through prior beliefs, social identities, circulating narratives, and existing information ecosystems (Adams et al., 2023). Without an intentional framework, even the strongest scientific evidence can be misunderstood, ignored, or selectively interpreted in ways that undermine its impact.

A framework for durable science communication

To move from information delivery to sustained understanding, science communication benefits from structured, research-backed frameworks. These frameworks move beyond the simple dissemination of facts toward intentional ecosystems that prime audiences to receive information in ways that meet them where they are. By integrating strategy, context, and continuity, such systems support understanding that endures.

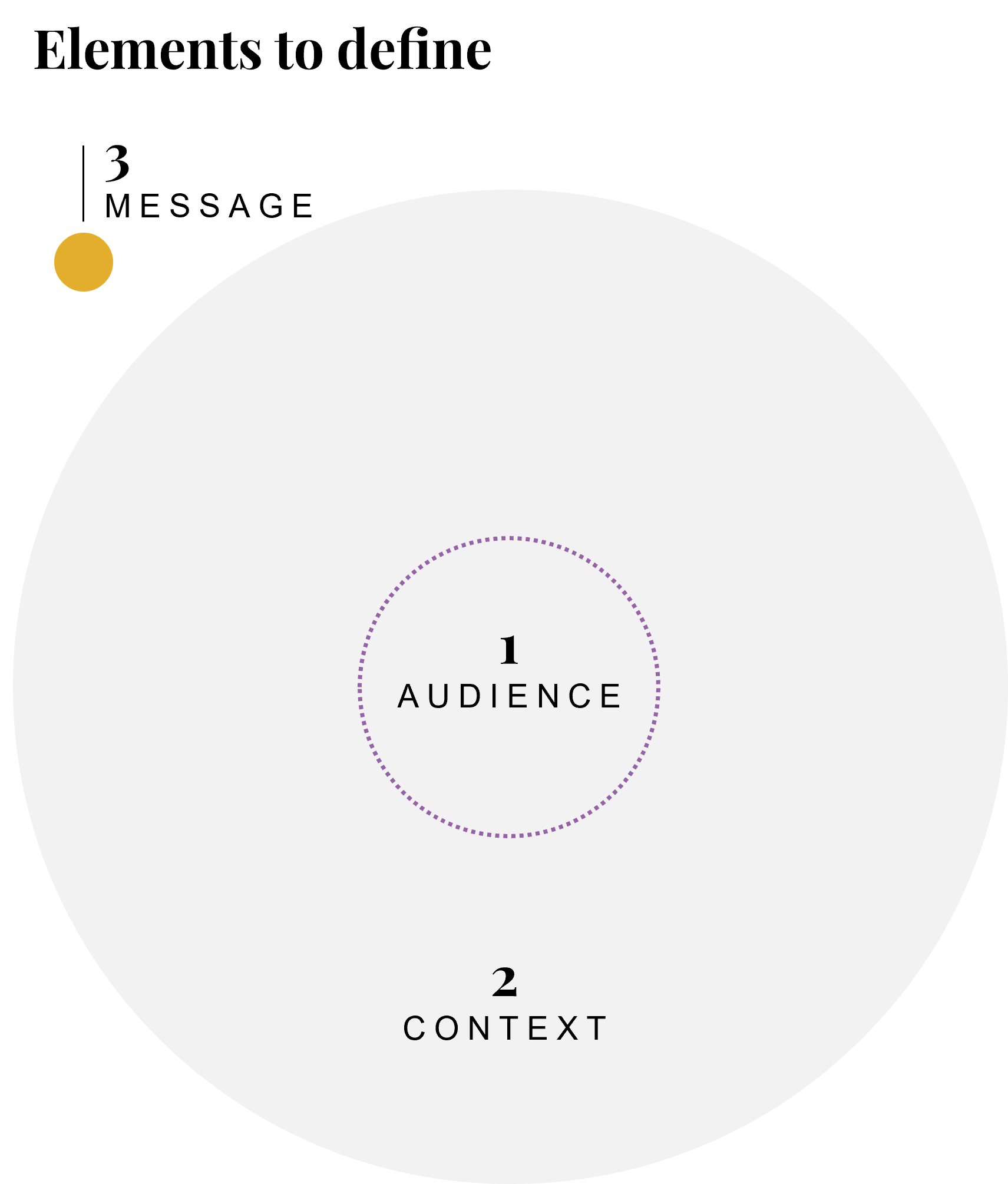

A practical model we use at Stellate Communications includes five elements:

1. Audience

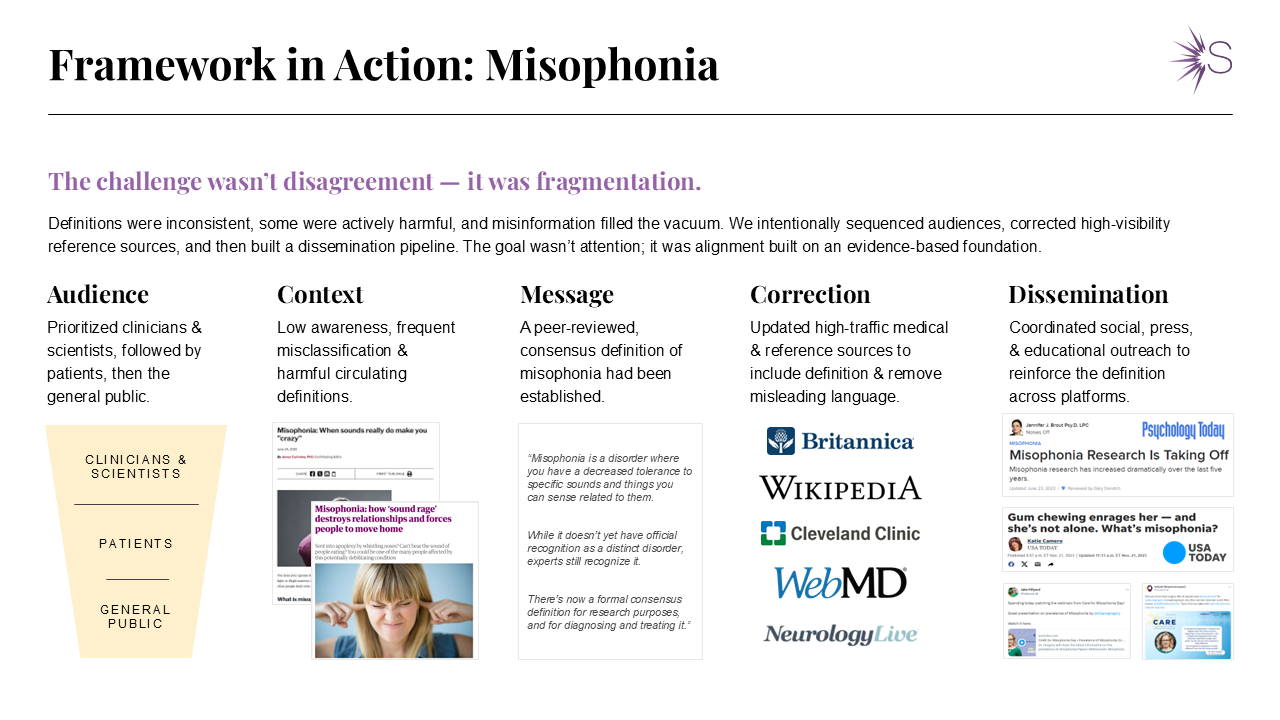

Effective communication begins by defining a single primary audience—the group that must understand the information for the intended goal to be achieved. For example, when a new clinical consensus definition is established, broad awareness and alignment among clinicians and researchers is a necessary first step. These audiences shape diagnosis, research standards, and downstream interpretation and without their awareness and buy-in, broader understanding cannot take hold.

In the case of misophonia, in partnership with the Misophonia Research Fund, clinicians and researchers were prioritized as the primary audience when a formal definition for the disorder had been published, followed by patients as a secondary audience—many of whom may not yet recognize the condition or understand its clinical basis. One message and delivery system designed to reach clinicians, patients, and the general public will inevitably miss the mark for all three. Secondary and tertiary audiences can and should follow, but only once the primary audience is clearly defined and held as the priority.

Trying to speak to everyone at once almost always results in clarity for no one.

2. Context

A common communications principle that is often used as the next step is “tailoring the message to the audience.” While this step is necessary, it misses an often overlooked consideration: audience alone does not determine how information is received — context does.

Context determines how information is interpreted before it is even evaluated for accuracy. This includes existing beliefs, identity-based commitments, and pre-existing dominant narratives. Context adds an additional layer to your primary audience. It’s no longer just “clinicians,” instead it becomes: “primary care physicians who encounter patients for whom specific sounds—such as chewing or pen clicking—trigger strong negative emotional, physiological, and behavioral responses, as seen in misophonia, yet who are unfamiliar with the disorder.”

These distinctions matter. Understanding context allows communicators to anticipate friction points and design messages that can be absorbed rather than immediately rejected.

3. Message

The message sits at the intersection of what is true and what an audience can realistically find (where they look for information) and absorb (what they are prepared to accept) within their current context.

For primary expert audiences, such as clinicians, evidence and consensus definitions may be sufficient to establish understanding. These audiences already share the conceptual frameworks needed to interpret technical language accurately. In these cases, the challenge is often less about belief and more about visibility: whether accurate information is present in the sources they routinely consult.

As communication extends to secondary and tertiary audiences (i.e., patients and the general public) the role of narrative becomes more critical. Evidence from cognitive and communication science shows that narrative-based approaches can help scientific information cut through identity-based resistance by providing structure, meaning, and relevance (Dahlstrom et al., 2021). For example, narrative framing can help patients and families recognize that distress triggered by everyday sounds reflects an involuntary neurobiological response, rather than a behavioral choice or emotional overreaction.

The facts remain unchanged, but the framing determines whether they are understood and accepted by very specific audiences.

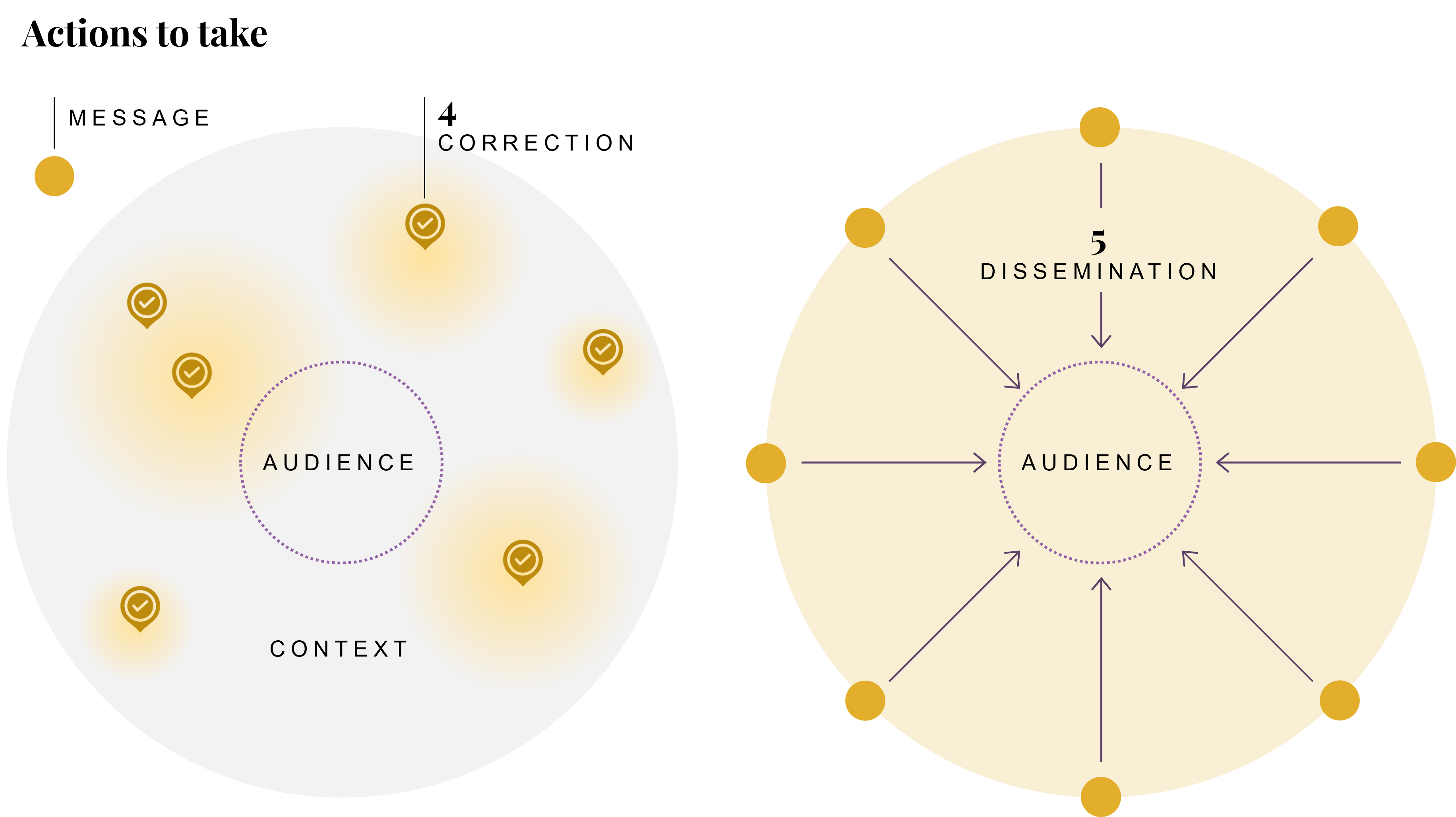

4. Correction

Correction is most effective when it strengthens trusted information rather than amplifying false or misleading claims. Improving the quality, consistency, and visibility of reliable sources over time has greater impact than reactive debunking alone (Ecker et al., 2022). The goal is to make accurate information easier to encounter than misinformation.

This begins by indexing what information already exists and where audiences are most likely to encounter it. In the case of misophonia, early descriptions framed the condition as “sound rage” or implied that individuals were “going crazy.” These framings persisted not because they were accurate, but because they occupied high-visibility news coverage in the absence of reliable, highly-trafficked reference sources.

For the defined clinician audience, correction efforts focused on the sources most commonly consulted during an online search, such as WebMD, Cleveland Clinic, and specialty outlets like Neurology Live. For patients and families, Wikipedia, social media, and mainstream media can be more accessible.

5. Dissemination

Research shows that misinformation is most effectively addressed not through one-off corrections, but through a steady stream of reliable, accurate information that becomes familiar, accessible, and easy to retrieve (Ecker et al., 2022). Dissemination is how accuracy becomes the default rather than the exception.

In practice, this means meeting audiences where they already look for information and sequencing channels to align with audience priorities. For the Misophonia Research Fund, dissemination began with research-facing press releases, professional meetings, and health and science trade media to reach clinicians and researchers first. From there, outreach expanded to mainstream media to reach secondary and tertiary audiences, including patients, families, and the broader public, increasing the presence of highly indexed, credible news coverage online.

Together, these efforts formed a dissemination pipeline across the digital landscape—one designed to reinforce accurate definitions consistently across platforms. Consistency, not “going viral”, is what builds credibility and durability over time.

Key takeaways

This framework is particularly valuable in situations where the primary challenge is not active disagreement, but fragmentation. In these cases, inconsistent definitions, partial explanations, and low-quality summaries create an information vacuum that misinformation quickly fills. The goal is alignment—built on an evidence-based foundation that can support education, policy, and practice over time.

Several principles emerge consistently from both research and practice:

- Facts alone are not enough—frameworks shape understanding

- Reliable information must be continuous, visible, and reinforced, not episodic

- Narrative structure helps evidence cut through identity-based beliefs

- Correction works best by strengthening trusted information, not amplifying misinformation

- Consistent, cohesive dissemination is how accuracy becomes durable

If science is to inform public understanding in a lasting way, communication must be designed as a system alongside it— not treated as an afterthought.

This framework was presented at the 2026 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology meeting as part of a Special Topics Session on science communication and combatting misinformation.